Insights

Will the UN Continue to Leave LGBTIQ Afghans Behind?

Region(s)

TOPIC(s)

Type

Commentary

Author(s)

Publish Date

February 13, 2024

Share

On February 18, senior officials from the United Nations and governments around the world will meet in Doha, Qatar, to discuss the ongoing crisis in Afghanistan. The date marks two and a half years of Taliban rule and the brutal suppression of the human rights of Afghans, especially women and girls, ethnic and religious minorities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) people. But will their voices be heard at the landmark high-level meeting in Doha?

The United Nations has undertaken various efforts to address what it describes as a human rights, governance, humanitarian, and development crisis “on an unprecedented scale.” It maintains a Security Council-mandated UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and has developed a Strategic Framework on Afghanistan based on the principle of “leaving no one behind,” while the UN Human Rights Council has appointed a Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan. In December, the Security Council adopted a resolution requesting the UN Secretary-General to appoint a Special Envoy for Afghanistan to oversee a path forward towards a “secure, stable, prosperous and inclusive” Afghanistan.

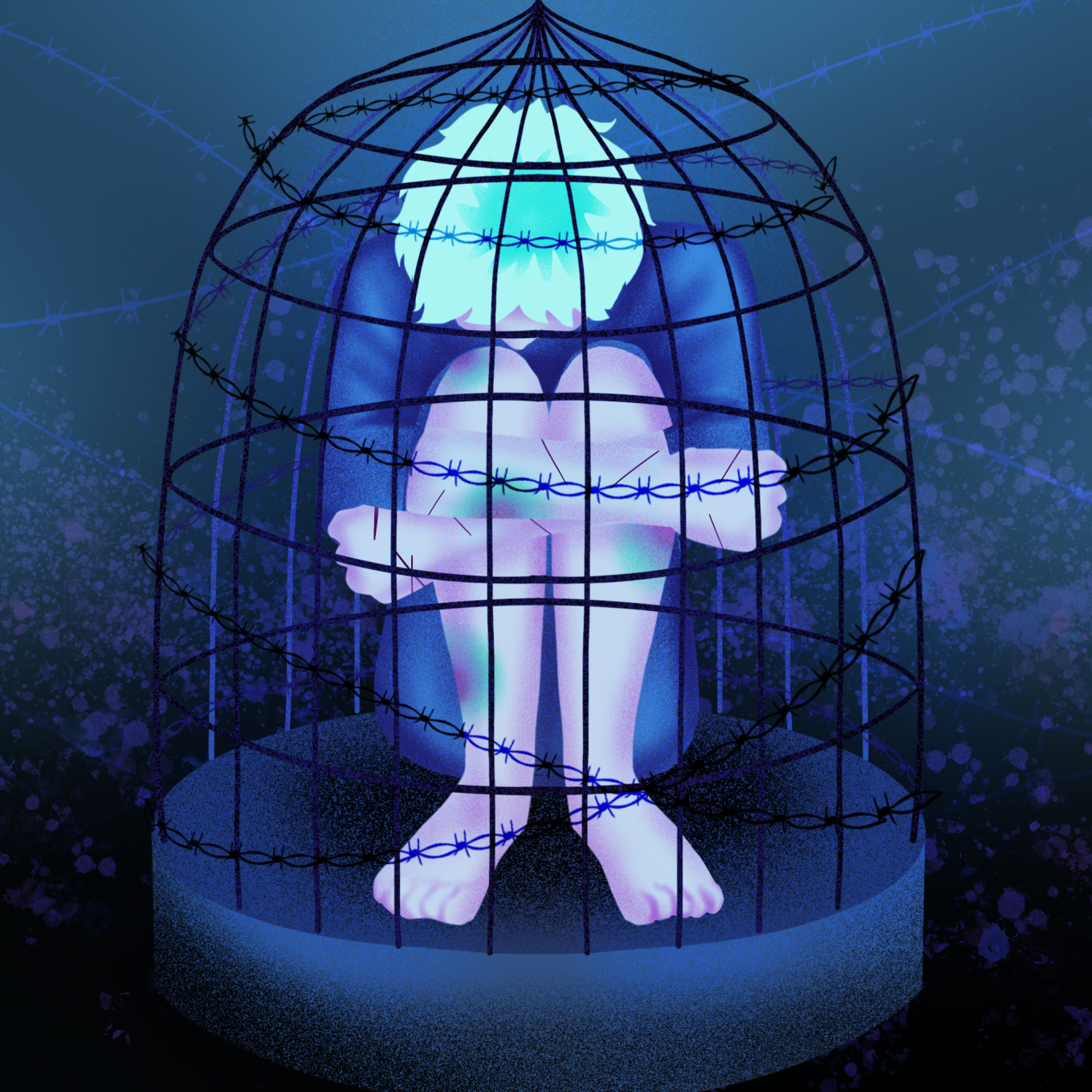

LGBTIQ people are among the most marginalized, excluded, and unsafe groups in Afghanistan. Outright International, the Afghanistan LGBT Organization (ALO), and others have documented how the Taliban has subjected LGBTIQ people to grave human rights violations including rape, arbitrary detention, torture, forced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and the issuance of death sentences. The UN, however, has repeatedly neglected LGBTIQ Afghans’ human rights. On February 7, we wrote to the Under-Secretary-General of the UN Department of Peacebuilding and Political Affairs, Rosemary DiCarlo, asking her to exercise her leadership to address this invisibility.

For example, UNAMA issued a detailed 2022 human rights report that entirely omitted the experiences of LGBTIQ people, despite chapters dedicated to discussion of gender-based violence, the prosecution of “moral crimes,” and the problematic role of the Taliban’s Ministry on Virtue and Vice. UN Women has issued compelling denunciations of gender apartheid and other violations against Afghan women, but does not speak to the specific experiences of lesbian, bisexual, or trans women or how gender persecution impacts LGBTIQ communities in Afghanistan.

The Special Rapporteur on human rights has, laudably, acknowledged and reported on violence against LGBTIQ people in Afghanistan and how it impacts lesbian, bisexual, trans, and gender-diverse Afghan women specifically, although the official UN translations of his reports in Dari and Pashto are blighted by the use of derogatory terms. The UN Strategic Framework lists sexual and gender minorities among the groups in Afghanistan that must not be left behind, but sets forth no approach to address their victimization and exclusion.

In March 2023, the Security Council called on the UN Secretary-General to conduct an independent assessment “to address the current challenges faced by Afghanistan, including, but not limited to, humanitarian, human rights and especially the rights of women and girls, religious and ethnic minorities, security and terrorism, narcotics, development, economic and social challenges, dialogue, governance and the rule of law.” The Security Council resolution specifically emphasized the importance of “upholding human rights, including those of women, children, minorities, and persons in vulnerable situations.”

Our LGBTIQ communities have never been visible in Security Council resolutions, but we hoped that this language might be inclusive enough to allow for LGBTIQ voices in the independent assessment. In response to an open call for Afghan civil society participation in consultations with the Special Coordinator’s office, Outright and ALO proposed a separate consultation for LGBTIQ Afghans, who would not be safe or able to speak freely in a general civil society meeting. The Special Coordinator’s office agreed, holding the LGBTIQ consultation virtually on 24 September. Fourteen LGBTIQ Afghans participated, subjecting themselves to the risk of retraumatization by recounting the grave human rights violations they faced under Taliban rule. They also shared key recommendations, among them: conditioning engagement with the Taliban on their respect for human rights, including the rights of Afghan LGBTIQ people; holding the Taliban accountable for crimes against women, girls, and LGBTIQ people, including crimes that amount to gender persecution and gender apartheid under international law; and engaging consistently with civil society organizations that work for LGBTIQ people in Afghanistan. But in the final independent assessment report, the only reference to LGBTIQ people is a footnote mentioning the consultation participants’ nonbinary gender identities. Elsewhere, the report writes LGBTIQ Afghans out of its frame of reference. It contains no reference to human rights violations experienced by LGBTIQ Afghans and no commitment to remedy these abuses, in contrast with its discussion of the human rights of women, girls, ethnic and religious minorities, and journalists.

If the UN is truly committed to an inclusive Afghanistan, it must rectify its own persistent exclusion of their voices. The Doha high-level meeting is one place to start. The UN is inviting civil society activists to the meeting. An Afghan LGBTIQ activist should be among them. In addition, the human rights of LGBTIQ people must be on the table at Doha, including in discussions with Taliban leaders, if they attend the meeting. The international community must make clear to the Taliban that death sentences for consensual sexual acts are unacceptable and that no one, of any sexual orientation or gender identity, should be subjected to torture, sexual violence, or arbitrary detention.

If Secretary-General Antonio Guterres proceeds to appoint a UN Special Envoy on Afghanistan, he must only consider candidates that are willing to uphold human rights for all, including LGBTIQ people. And the new Special Envoy must be willing to meet with LGBTIQ Afghans and take steps to ensure their protection and inclusion. The creation of a Special Envoy will be meaningless for LGBTIQ people if there is no intention to engage with them substantively and take up the appalling level of violence against them.

Whatever the division of labor may be between an eventual UN Special Envoy and the existing UNAMA mission, both bear a duty when it comes to addressing the human rights and security of all Afghans, including LGBTIQ people.

Any other approach sends a signal that the UN considers certain voices dispensable, reinforcing the very exclusion and discrimination to which the Taliban subjects LGBTIQ people on a daily basis. We cannot achieve inclusive and enduring peace and security in Afghanistan as long as the UN itself accepts the marginalization and invisibilization of a sector of society.

Take Action

When you support our research, you support a growing global movement and celebrate LGBTIQ lives everywhere.

Donate Now